Burt Saxon

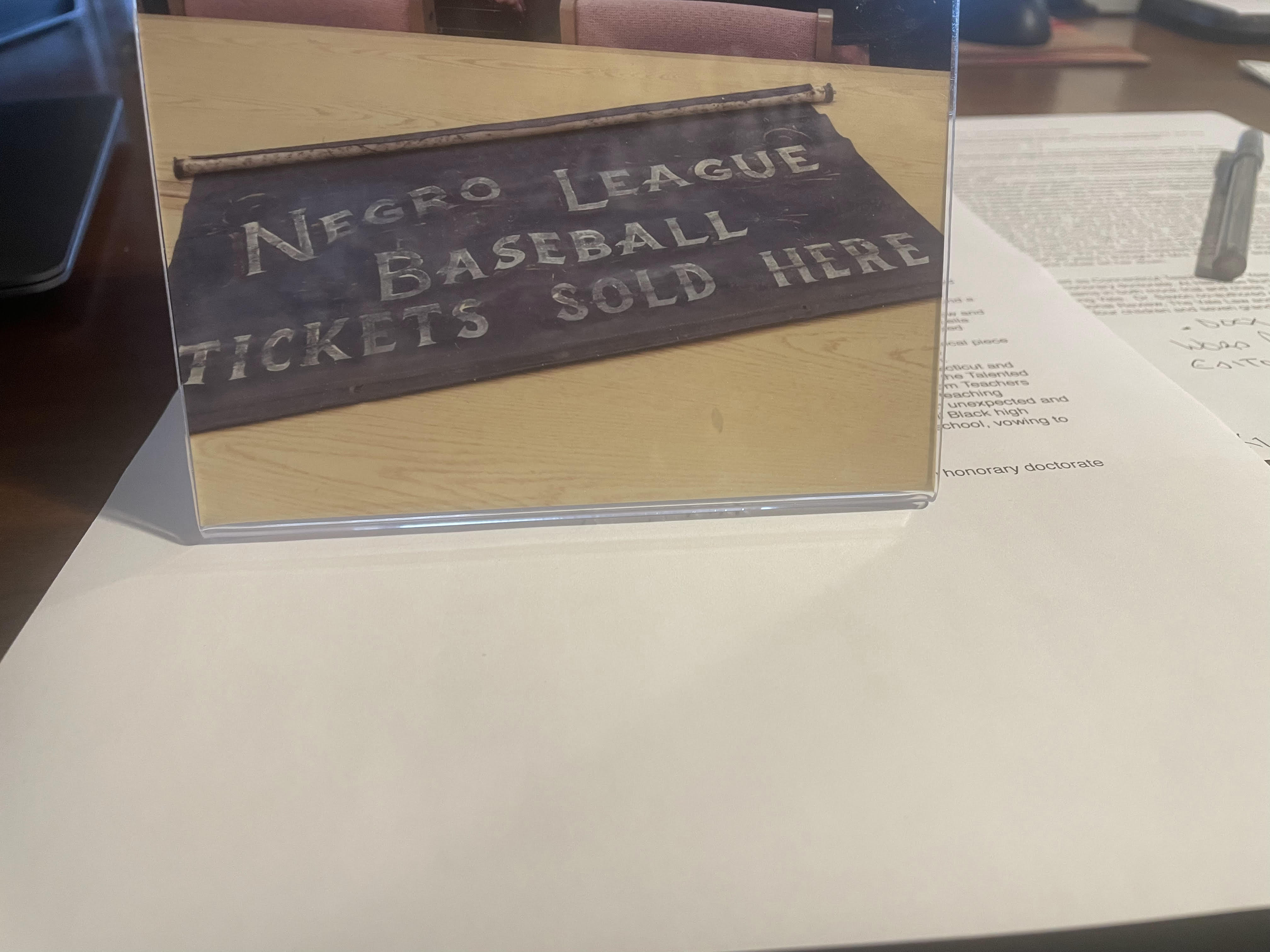

One summer morning in 2010 I walked into Salvage Alley, an aptly named antique store, and saw a black window shade with gold lettering hanging from the rafters. The inscription read:

Negro League Baseball Tickets Sold Here.

This looked like the real deal, but the store owner told me the shade might be a forgery. Every sports memorabilia collector knows Negro League memorabilia is frequently forged. The shade's asking price-$250- was a lot of money for a retired public-school teacher, but I came back the next day with the cash.

A couple years later two appraisers were pretty sure the shade was authentic and estimated its value at $3000-$8000. I decided to donate the shade to either the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, or the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. Neither museum returned my voice mail. Clearly the curators thought I owned a fake. So, I put the shade in a closet.

In 2015 my grandson Colby's Little League team was headed for Cooperstown to play in the Field of Dreams tournament. I called the Hall of Fame again. The curator said she would look at the item. She accepted the shade as a donation and gave me a lifetime pass to the Museum. A month later she emailed me and said a chemical analysis had shown the shade came from the 1930s. I later found a picture of the shade on a ticket window in the South.

My accountant is a baseball fan. He told me my proposed tax deduction of $3000 was too low and suggested I have the shade appraised. The Hall of Fame suggested I contact their appraiser, Leila Dunbar. She sent me a detailed report placing fair market value at $25,000. At a well-publicized auction, I believe the window shade would have sold for far more than 25K.

One of my friends asked why I donated such a valuable item. I answered that this historical piece belonged to the American public. I did not want it to end up in someone's fancy man cave.

There was another reason I gave away the Holy Grail- a much more personal reason. Emma Ruff was one of the very first African-American teachers in New Haven, Connecticut, and the first female high school principal in our state. She hired me as teacher/facilitator of the Talented and Gifted program at Hillhouse High School in 1980.

After I received my doctorate from Teachers College, Columbia University in 1977, two East Coast universities denied me college teaching positions. Both cited DEI concerns. How ironic that a Black woman would give me an unexpected and ideal opportunity to teach the so-called talented tenth of the students in a virtually all-Black high school. For the next 26 years, I thought of Mrs. Ruff every single day I entered the school, vowing to do my very best and to never let her down.